The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Historic Transformations in Medicare, Rx Drug Pricing and the Affordable Care Act

.png)

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) includes arguably the most significant changes to the U.S. prescription drug policy since the creation of the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit in 2003. This blog post explores the details of the prescription drug policies, including Medicare negotiation, inflation caps, Part D benefit redesign, insulin caps, free vaccines for Medicare beneficiaries, delay of a prescription drug rebate rule, and the Part D low-income subsidy. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the prescription drug policies will yield approximately $288 billion in savings over the next decade.

HHS will negotiate prices on high-cost drugs

The IRA requires Medicare to negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies on drug list prices—an action that has been prohibited since the Medicare Modernization Act was passed in 2003. The law redefines the “noninterference clause” to require the Secretary of Health and Human Services (Secretary) to directly enter negotiations with manufacturers of Medicare Part B (i.e., drugs often administered by a health care provider) and Part D drugs (i.e., medications prescribed at the pharmacy counter) to lower prices.

The Secretary can only negotiate the prices of 10 drugs at first and will work up to negotiating the prices of 20 drugs by 2029. Each year, the Secretary will select a certain number of drugs from a list of 50 “negotiation eligible” drugs in both the Part B and D programs. Drugs eligible for Secretarial negotiation must meet several factors:

the drug must be among the most expensive to Medicare;

lack generic or biosimilar competition;

be on the market for nine years (small molecule) or 13 years (biologics);

not have an “orphan designation” from the FDA as the only approved indication; and

not be on the small biotech exempt list.

Drugs selected to be negotiated will be subject to a “maximum fair price,” which is the price ceiling that drug manufacturers can sell the selected drug to Medicare. The maximum fair price will be based on the non-federal average manufacturer price and the length of time since the drug was approved by the FDA.

Manufacturers that refuse to comply with the maximum fair price or engage in negotiation will be subject to civil monetary penalties and an excise tax. The civil monetary penalties are ten times the difference between the maximum fair price determined by the government and the price set by the manufacturer for each unit of the selected drug furnished, dispensed, and administered. The excise tax would range from 65 percent to 95 percent of the drug price, increasing as non-compliance continues.

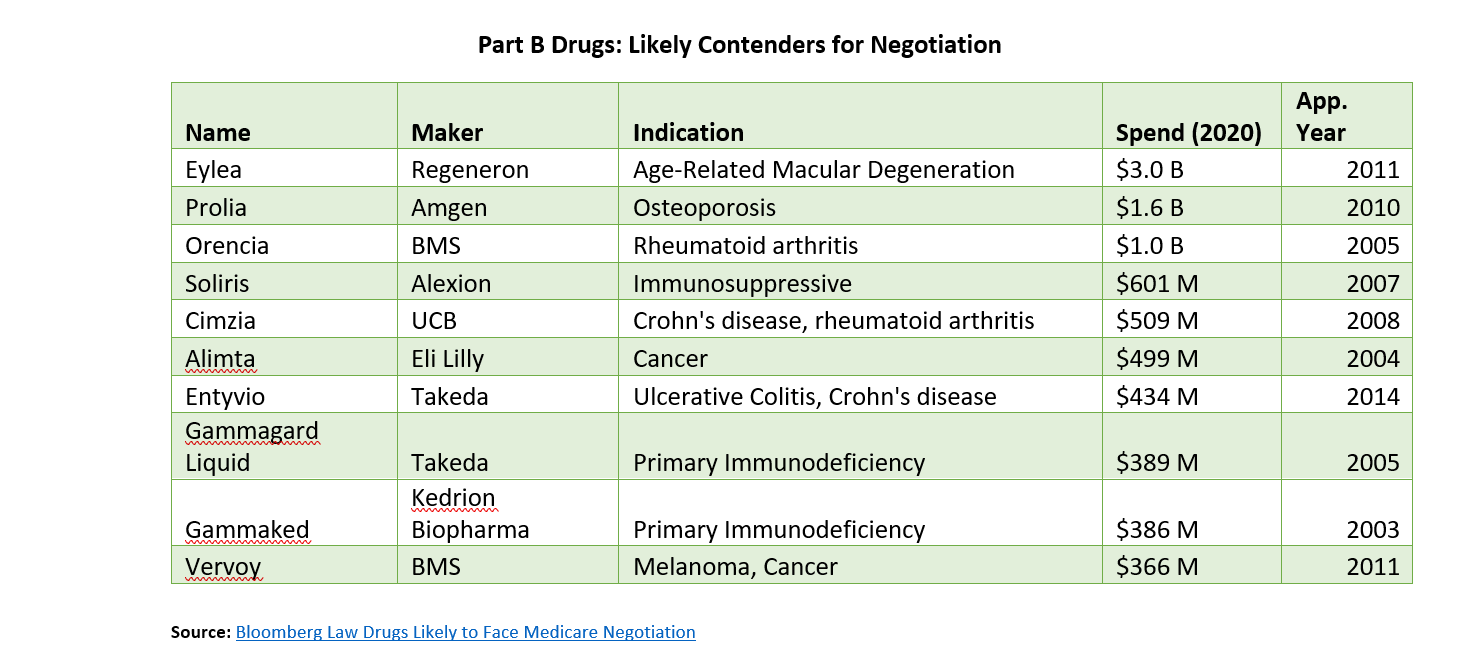

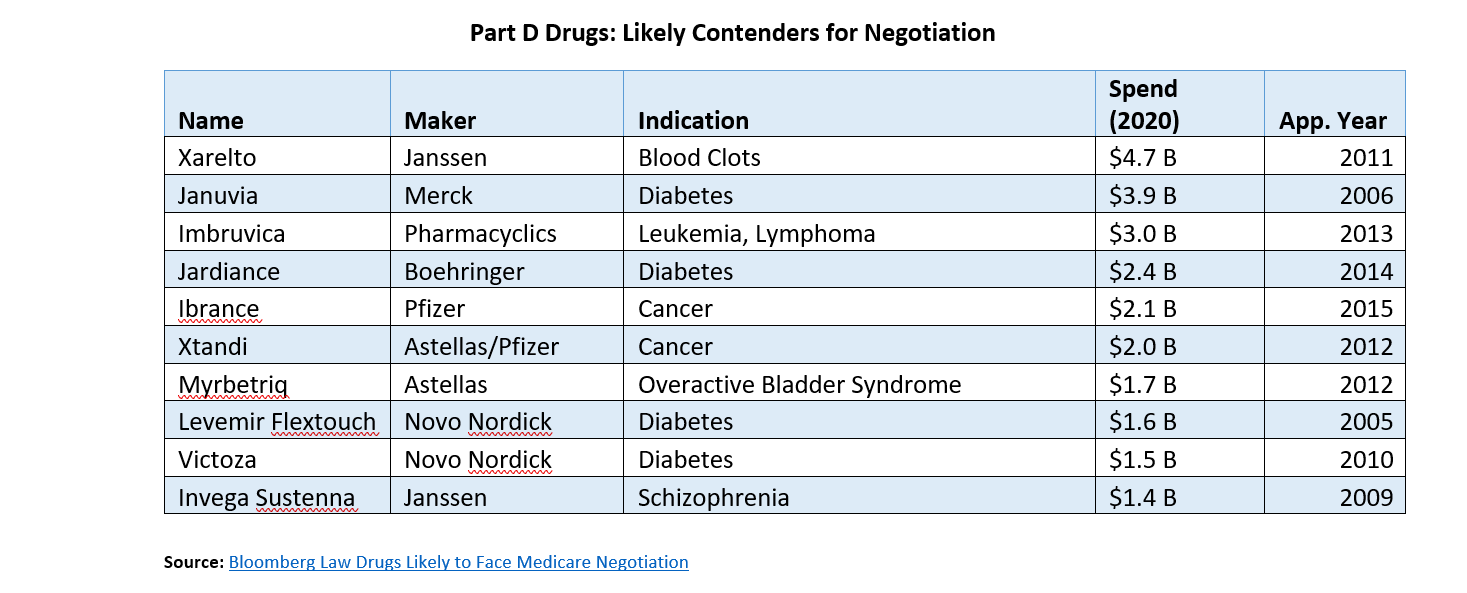

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) will reveal the first ten drugs that will be negotiated in September 2023, with negotiated prices going into effect in 2026. The process for selecting drugs to negotiate will likely be complicated and politically fraught. The IRA included $3 billion in funding for CMS to craft and staff a negotiation process. Below is a list of drugs likely to be subject to negotiation.

Drug prices hikes cannot exceed inflation

The IRA requires drug manufacturers to pay rebates to the federal government if their single source Medicare drug prices rise faster than inflation. A manufacturer that does not pay the rebate within 30 days of notice from CMS will be subject to a penalty of at least 125 percent of the rebate amount. According to survey data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, half of all Medicare drugs had price increases between 2019 and 2020 that exceeded the inflation rate. This provision will be implemented in 2023.

While this provision will help reduce prescription drug price hikes in Medicare, there are two key concerns about how pharmaceutical companies will react. First, drug makers may seek to offset lost revenue by increasing the launch price of new drugs. Second, drug makers may cost-shift by increasing the price of drugs in the private market to compensate for lost revenue in the Medicare market. Senate Democrats had tried to apply the inflation rebate to the private market; however, the provision did not comply with Senate rules and was ultimately removed.

Beneficiary out-of-pocket costs are capped at $2000 per year

The IRA redesigns the Part D benefit to limit beneficiary out-of-pocket costs, decrease Medicare spending, and increase the liability for health plans and drug makers. Most notably, the IRA puts an annual limit on what Part D beneficiaries will have to pay out of pocket for their prescription medications. Previously, beneficiaries would have to pay 5 percent cost-sharing in the catastrophic phase of the benefit, with some patients paying thousands annually for their drugs. Starting in 2024, patients will not have to pay for their medications in the catastrophic phase. Then in 2025, patients will have their out-of-pocket costs capped at $2,000.

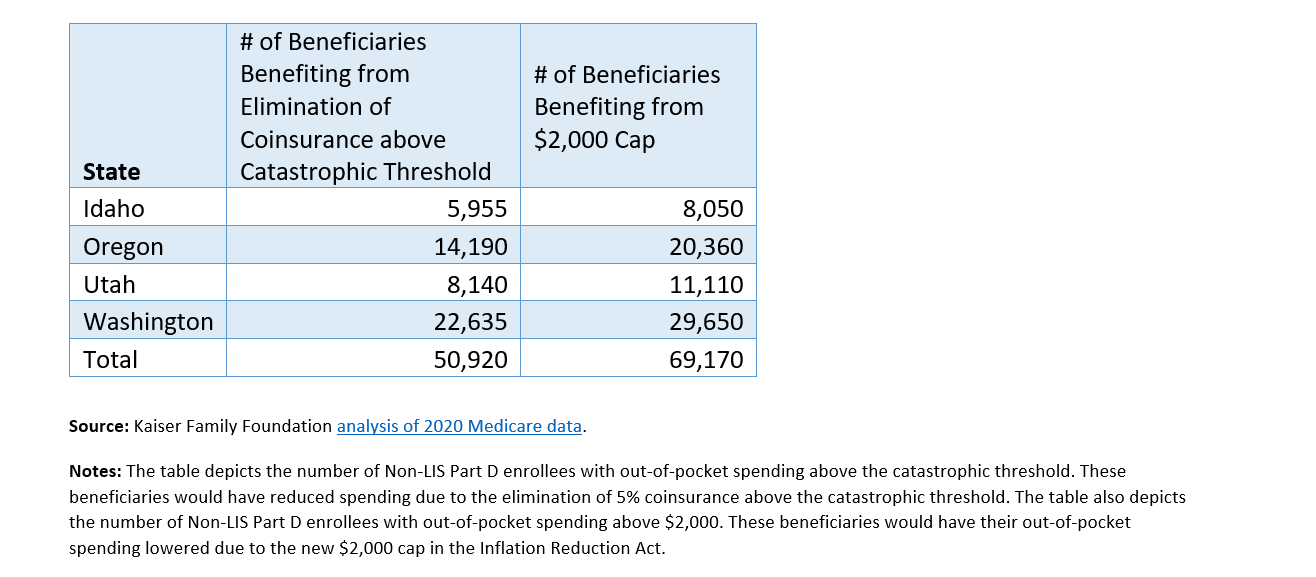

The elimination of coinsurance above the catastrophic threshold (beginning in 2024) and the $2,000 out-of-pocket cap (starting in 2025) will provide Medicare beneficiaries with significant financial protection from high Part D drug costs. The below chart shows the potential impact of these protections for people living in Cambia’s four-state footprint.

The bill also includes a deductible “smoothing” provision. Implementing this provision is likely to be complicated for pharmacies and insurers. Starting in 2025, this benefit will allow beneficiaries with high drug costs to spread their costs over the remainder of a plan year in monthly installments (e.g., a $1,200 bill in January could be paid $100 monthly). Beneficiaries can opt-in to this capped payment option during any point in a plan year.

Before the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, MedPAC and other policy experts argued that the Part D benefit design needed to be restructured to moderate price growth. In the new Part D benefit design, Medicare and patients will pay substantially less, while insurance plans and pharmaceutical manufacturers will pay significantly more for prescription drugs.

Medicare insulin costs capped at $35 per month

Starting in 2023, the IRA includes a cap on out-of-pocket insulin spending in Medicare to $35 per month. Then in 2026, insulin prices will be capped at the lesser of $35 or 25 percent of the maximum fair price. A provision that would have applied the $35 monthly cap to the private market was removed because it did not comply with Senate rules. Currently, one in five people prescribed insulin products with private health insurance pay more than $35 per month, and Medicare patients paid an average of $54 for insulin in 2020.

Vaccines will be provided without cost-sharing

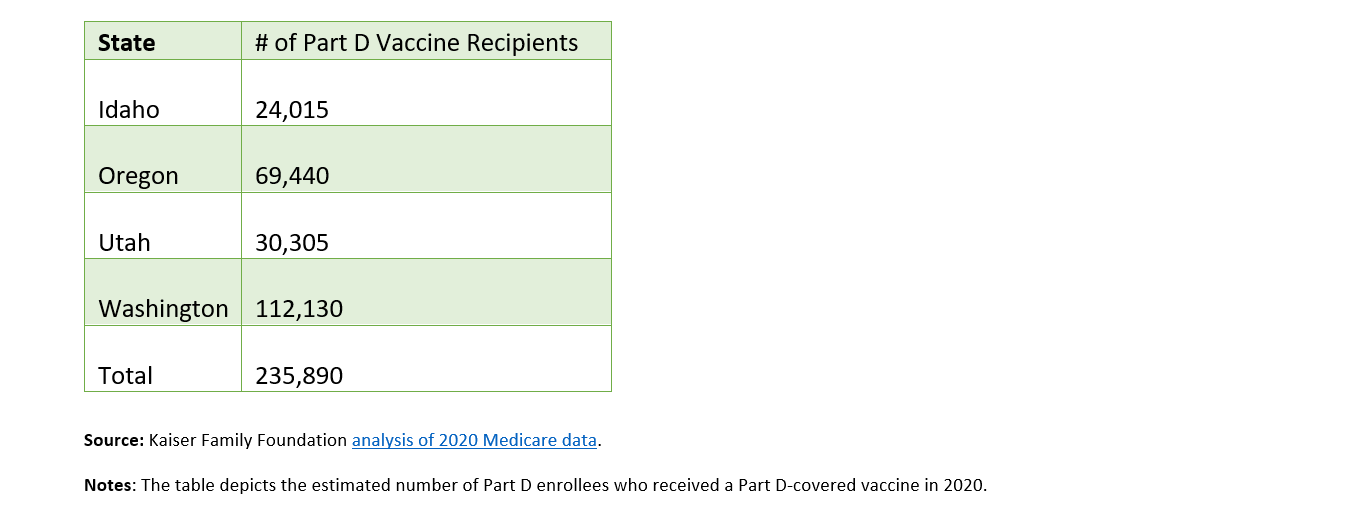

Starting in 2023, adult vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) under Part D will be provided to beneficiaries with no deductibles or deductibles. The legislation allows access to adult vaccines under Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) by providing enhanced federal reimbursement for providers. The below chart shows the potential impact of these protections for people living in Cambia’s four-state footprint.

Rebate rule is delayed again

To pay for many of the healthcare provisions in the bill, the IRA delays the Trump Administration’s rebate rule from 2027 to 2032. This rule, which has never been implemented, eliminates the anti-kickback safe harbor protections for prescription drug rebates negotiated between drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers or health plans. Without those protections, drug rebates would be applied at the pharmacy counter instead of used to reduce premiums for all enrollees.

More people qualify for Part D Low-Income subsidy

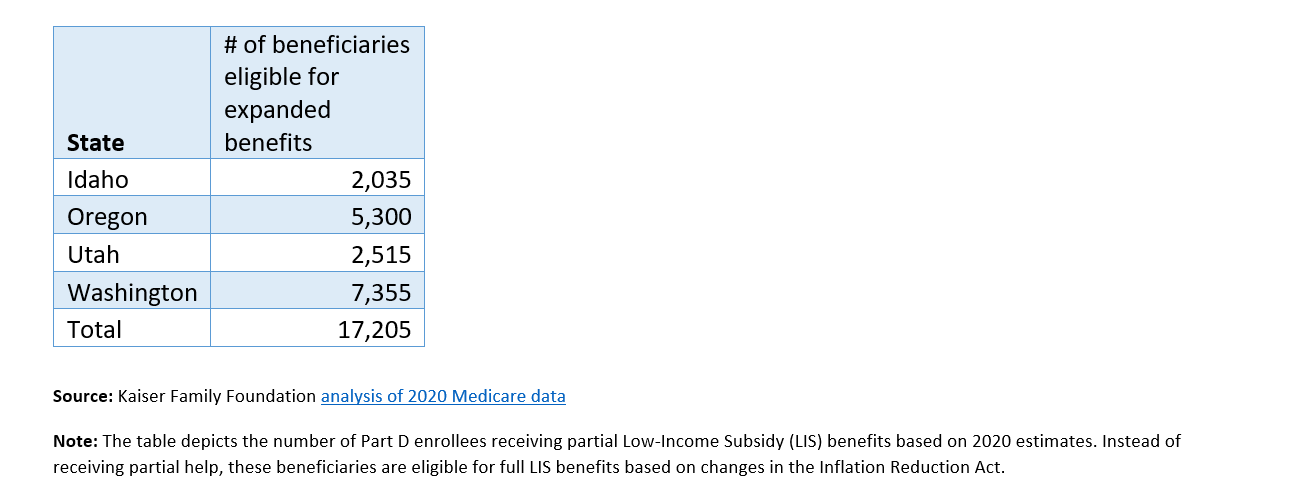

Starting in 2024, the IRA expands eligibility for the full Low-Income Subsidy in Part D (also called Extra Help Program) from people at 135 percent of the federal poverty line to 150 percent. For 2022, this would apply to individuals making $20,385 or less. It is expected that about 400,000 people will benefit from this expanded eligibility. The below chart shows the potential impact of expanded Low-Income Subsidy for people living in Cambia’s four-state footprint.

The road to implementation

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act into law is only the beginning of its story. The rollout of the law’s provisions is scheduled to take place over years. During this time, HHS must develop and issue proposed regulations, subject to review and the consideration of public feedback, before all of the law’s provisions are fully implemented. We anticipate the law could face legal challenges from drug manufacturers and other stakeholders on drug price negotiation that could affect implementation (including the selection of drugs for negotiation and the calculation of a drug’s maximum fair price). Finally, the results of future Congressional and Presidential elections could impact how the law’s provisions are enforced. But in the absence of any major changes, the Inflation Reduction Act will significantly alter Medicare, drug pricing, and the ACA marketplace for years to come.